To Swallow A River

The Zen koan that — may have — turned a samurai into a hermit

While recounting the story of my favorite hermit (and — dare I say it — possible role model sigh), I mentioned how, as a boy of just twelve, he abruptly left the samurai path to live as a lay hermit.

What could have led someone so young, in the rigid world of warrior training, to make such a radical turn? Especially in 1582 — two decades before the Tokugawa era began, when Japan would enter a long period of peace and many samurai, no longer needed for warfare, turned to administrative work or spiritual pursuits, like the komusō monks.

There is no definitive answer, but a possible clue was inscribed on Sokun’s tombstone — a Zen fable, known as Saikō-sui (西江水), or “West River Water,” which may have played a role in his transformation.

Even though we may never know whether it’s true, the story itself gripped me.

And so, I’d like to share it with you.

Saikō-sui

Saikō-sui refers to a famous Zen kōan, or saying.

The phrase originates from a dialogue in Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism: Layman Pang (龐居士, Pang Yun, 740–808) — a renowned lay Zen practitioner — once asked the great Master Mazu Daoyi (馬祖道一) a profound question.

Pang inquired:

“Who is the one who is not a companion to the ten thousand things?”

(i.e. who is independent of worldly phenomena)

In reply, Mazu said:

“Wait until you can swallow all the water of the West River in one gulp, then I will tell you.”

Or in Chinese: 「一口吸盡西江水」 (yīkǒu xījìn Xījiāng shuǐ)

Meaning: “To swallow all the water of the West River in one mouthful.”

This exchange is recorded in the Records of Mazu.

Historically, Layman Pang is a real figure in Tang-dynasty (618–907) Chan Buddhism.

In Japanese Zen circles, the phrase — read as Saikō-sui — was known as a kōan.

Interestingly, this kōan was wrestled with by none other than Sen no Rikyū, the 16th-century tea master.

Rikyū, well-versed in Zen, became tea master to Oda Nobunaga in 1579, and later to Toyotomi Hideyoshi after Nobunaga’s death in 1582.

It’s therefore possible — even if only speculatively — that Sōkun may have encountered Rikyū, or at least been influenced by the same Zen culture in which Saikō-sui was circulating.

But I digress.

The Meaning of the Kōan

The West River water story carries deep Zen significance.

Let’s break it down together.

When Layman Pang asks how to find a person free from all worldly attachments, Master Mazu’s startling reply — “I’ll tell you after you drink up the entire West River” — is not a literal challenge. It’s a mind-shattering one.

This is classic Zen: Mazu does not explain with reason or logic, but delivers an “impossible” task to shatter dualistic thinking.

The impossibility is the point — true awakening cannot be grasped through reason alone.

One interpretation is that to be unattached to the “ten thousand things,” one must become so unified with everything that no separation remains — metaphorically, “swallowing the world.”

In other words, Mazu implies that enlightenment is not found by escaping the world, but by transcending the self-world duality — embracing reality so fully that nothing is outside oneself.

Faced with this challenge, Pang suddenly attained great insight.

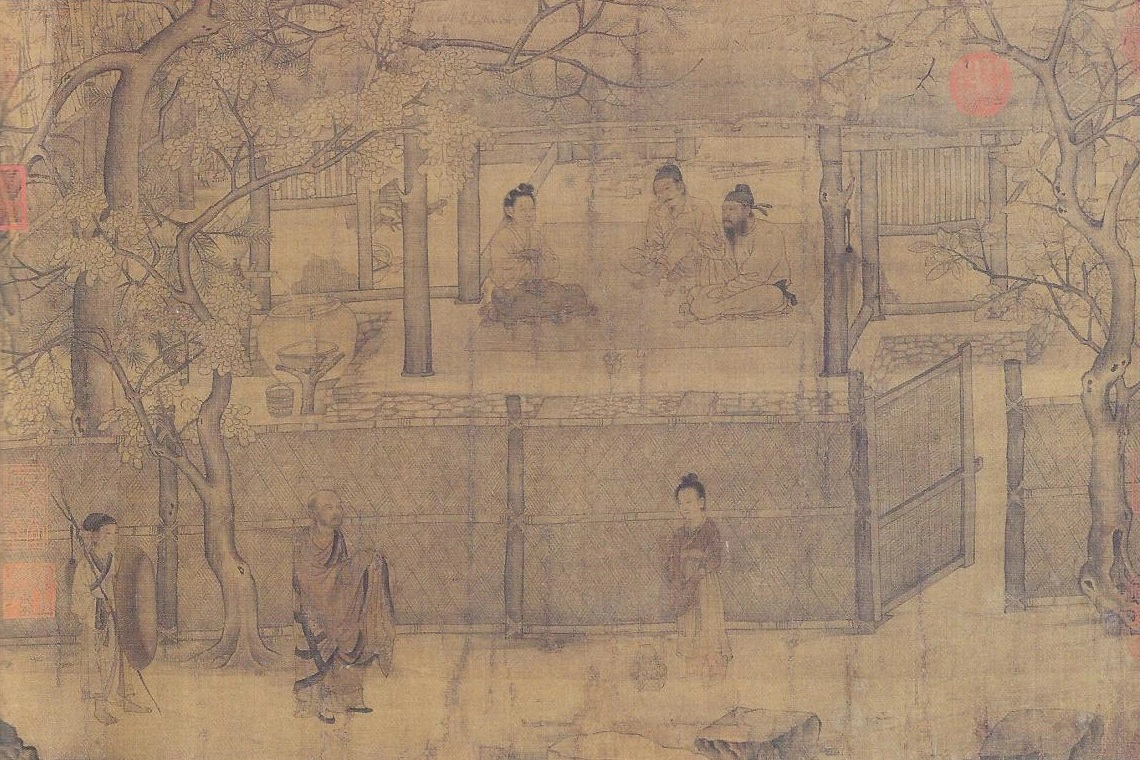

Danxia Tianran visits Layman Pang 丹霞天然問龐居士圖 - Attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 (d. 1106), 13th or possibly early 14th century

Handscroll, ink and light clours on silk, 35.2 x 52.1 cm - Public domain.

Image source: Terebess Asia Online.

Danxia Tianran visits Layman Pang 丹霞天然問龐居士圖 - Attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 (d. 1106), 13th or possibly early 14th century

Handscroll, ink and light clours on silk, 35.2 x 52.1 cm - Public domain.

Image source: Terebess Asia Online.

Layman Pang’s Inspiring Perspective

After this encounter, Layman Pang composed a verse that reflects his realization:

“All across the universe people in their way seek the Dharma;

[Yet] each and every one learns without doing (wu-wei).

This — right here — is the place to select a Buddha;

Empty-minded, I return home with nothing to attain.”

He also famously said:

“How miraculous, how wondrous — I carry wood, I draw water!”

His “miracle” wasn’t in a mystical power, but in recognizing the sacred within the mundane.

Nothing in his daily routine changed — except his mind.

Chopping wood, drawing water — these, too, were the Way.

Pang reportedly cast his fortune into a river and took up humble work, making wooden utensils to support himself.

His teachings were not given in sermons but lived through example and short, pithy dialogues.

He demonstrated that a layperson could awaken fully — and “live Zen” in everyday life.

This made Pang a beloved figure in Zen tradition — a historical yet legendary model of freedom through simplicity.

In Japanese, he is known as Hōkoji.

Ōmori Sōkun and the Influence of the “West River” Story

We may never know for sure whether the Saikō-sui kōan truly inspired Ōmori Sōkun to renounce the samurai path and embrace a life of music and inner cultivation.

But the parallels are striking.

Just as Layman Pang let go of his wealth and status, Sōkun gave up his samurai rank and embraced the lifestyle of a kōji — an unordained hermit.

From that point on, he devoted himself to Zen and music, treating the flute as more than a tool for entertainment. It became his practice — a bamboo mirror of breath, silence, and spirit.

He studied old melodies, composed new ones, and passed down his style — known as Sōkūn-ryū, or more famously, Sōsa-ryū — to his son and disciples.

Sōkun’s dedication suggests that, for him, the flute was not just an instrument, but a way of life.

The West River kōan may have affirmed what he already sensed:

That meaning is not found in titles or wealth, but in the quiet, persistent act of breathing into the world — one note at a time.

And that’s quietly profound, isn’t it?

Sources

- Shin Sosa Ryu hitoyogiri school - www.hon-on.com

- Terebess - https://terebess.hu/zen/pang.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Rinzai school - Engaku-ji (Kamakura) https://www.engakuji.or.jp/blog/36376/