“Recluses, Wanderers, Ascetics”

Three faces of retreat in Edo Japan—and the single thread I follow through them: a simple life to listen more clearly.

Hello, friend —it’s been a while! Well, I wasn’t exactly twiddling my thumbs. Plenty of brain-whirring going on here, plus a few technical glitches: a new flute, videos, the bathroom fuse tripping, cold showers because the boiler is sulking… you know, life.

And while I was battling electrical and plumbing emergencies, something kept poking at the back of my mind. I decided to follow the thread and share the result with you, my dear reader.

You know how much I love hermits (or at least what I tend to call a “hermit”—more on that in a minute).

Their philosophy fascinates me, but digging into Sōkun’s life also showed me my own blind spots (sigh).

For me it seemed obvious: living apart + a somewhat ramshackle hut + mountains = hermit. Case closed.

Wrong!

A quick note on terminology

In this post, I use “hermit” in a broad sense to mean different forms of voluntary retreat. It’s a personal choice, and it’s imprecise.

If we want to be accurate about the people I’m discussing:

- Bashō fits better as a recluse poet (sōan on the edge of town) than a monastery-style hermit.

- Issa is best described as an itinerant/peasant poet, very much among people.

- For Ōmori Sōkun, there’s no solid proof he was a hermit: he is best described as a hitoyogiri master (Sōsa-ryū) who lived partly withdrawn while actively teaching and transmitting his art.

With that out of the way, it’s time to wrestle my old stereotypes (maybe yours too) and answer the question that’s haunted me these past weeks:

What actually defines these sages and artists who live at the edges of society? (And why do I care so much?)

I can hear you chuckle: if that’s my existential question… It’s barely better than wondering at 3 a.m. whether penguins have knees.

I checked. They do.

So there.

Recluses, wanderers, ascetics: shades of the same retreat

A hermit—or anyone who chooses retreat—is not necessarily “outside society.”

That idea doesn’t fit well with premodern Japan (Muromachi → Edo).

Take Bashō, a 17th-century (Edo) poet. His most famous haiku gives us the plop of a frog jumping into a pond. He lived in huts/ermitages—often on the town’s edge, where he still hosted poetry gatherings. Not exactly a wild man of the high peaks.

By contrast, Ryōkan (a Sōtō monk) and Issa chose a more “dynamic” retreat.

— Ryōkan: a monk-poet living simply, sometimes in a hut, often traveling, relying largely on alms.

— Issa: an itinerant poet, poor, close to everyday people, writing about ordinary life.

And then there’s Sōkun (late 16th–early 17th c.), a lay monk, hitoyogiri master and a leading figure of the Sōsa-ryū school. Nothing firmly labels him a hermit, but his path seems to oscillate between contemplative withdrawal, urban performances, and teaching.

Three ways of “stepping back,” three ways of living.

So… what unites them?

The many faces of retreat in premodern Japan

In very broad strokes (yes, I’m simplifying), we can sketch:

-

Itinerants & marginals (outside strict “hermit” status)

Drifters, people on the margins. Their isolation is often constrained, not chosen—so not hermits in the strong sense. -

Lettered recluses & artists

Aristocrats, scholars, poets, musicians who withdraw by conviction: some to protect their art from distraction (Bashō), others to focus on practice (masters like Sōkun). -

Religious & ascetics

Monastics for whom retreat is a discipline (short or extended retreats, ritual mendicancy, ascetic practice). Ryōkan sits largely here, while remaining close to people.

The ones who interest me most are those who choose solitude to hone the mind, the art, or a philosophical/inner ideal.

Whether secular (non-monastic) or religious, what unites them is a deliberately solitary and rather ascetic way of life.

What distinguishes them are their aims (art, wisdom, awakening…) and their ties to the world: some offer services (calligraphy, music), others live mainly on donations.

A working definition?

In Japan, from the late Middle Ages through the Edo period, I use “hermit” (in the broad sense) for someone who chooses seclusion to cultivate an art, a philosophy, and/or a spiritual path—including reclusion, itinerant life, and asceticism.

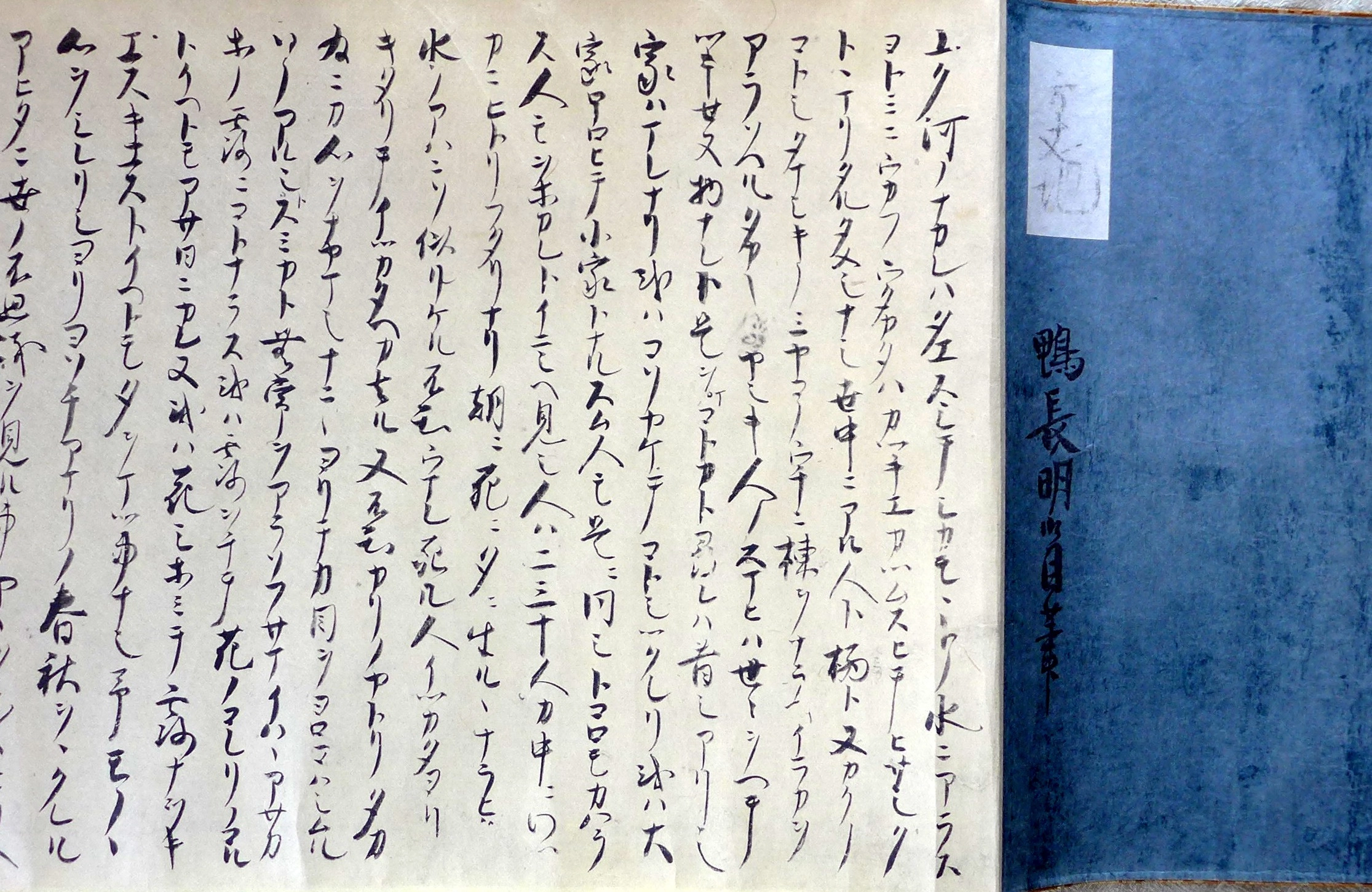

Manuscript page of the Hōjōki attributed to Kamo no Chōmei (Daifukukōji).

Kamo no Chōmei, Hōjōki (Daifukukōji manuscript, 13th c.) — Reproduction of a public-domain work. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Manuscript page of the Hōjōki attributed to Kamo no Chōmei (Daifukukōji).

Kamo no Chōmei, Hōjōki (Daifukukōji manuscript, 13th c.) — Reproduction of a public-domain work. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

What is their role in society?

Silly question? Look again. Hermits show up in every culture; they populate folktales and chronicles. And yet there are no “hermit schools,” guilds, or official status. Administratively speaking, a hermit is “useful” to no one and lives in a haze of ambiguity.

And still, they matter.

You find them in literature and painting; people even attribute miracles to them. Lords and rulers sought their counsel—not for a stamp of approval, but because their perspective was worth something.

What a (broad-sense) hermit offers

-

A clear vantage point

No head-down grind: a hermit sees reality with distance, free from the urban husstle and bustle. -

Sane values

Their renunciation reminds us how little we actually need to live fully—and that this “little” is unique to each of us. We have to find it for ourselves. -

The real questions

Hermits do what the people who keep society running rarely have time to do: stop. Face illness, injustice, old age, death, the meaning of life. When we lose our footing, they can bring us back to ourselves because they’ve looked long and hard within, and without.

Why this fascinates me (and maybe you)

To me, the hermit embodies:

- Courage — answering an inner call and honoring it despite discomfort.

- Resilience — sitting with fear and shadow until we stop fleeing them.

- Quiet — letting the mental noise slow down into a soft background hum.

- Solitude — not everyone’s favorite, I know, but it matters a lot to me.

Reading Brad Warner’s There Is No God and He Is Always With You, I found a line attributed to Kobun Chino that really resonated with me. I haven’t tracked it down elsewhere, but regardless of who said it first, I agree with the spirit of it:

Wanting to be alone is impossible. When you become really alone you notice you are not alone. You flip into the other side of nothing, where you discover everybody is waiting for you. Before that, you are living together like that — day, sun, moon, stars, and food — everything is helping you, but you are all blocked off, a closed system. It is very important to experience the complete negation of yourself, which brings you to the other side of nothing. People experience that in many ways. You go to the other side of nothing, and you are held by the hand of the absolute.

I don’t know about you, but some things are easier to see when I step back.

So yes, I think I understand these hermits, recluses, wanderers just a little—and I fully intend to keep diving into what they left us; each reread opens a new layer of understanding.

In the coming weeks, drop by my YouTube channel: I’m preparing a series of Shorts on some of those fascinating characters from the past, the ones who inspire me most—Ryōkan, Issa, Bashō, the “Hermit of Edo” (and the list keeps growing).

See you soon!